While doing some research for NSX setups I found the urge to delve deeper into the calculations of some of ESXi’s load-balancing and teaming types that are available, below I have outlined the scenarios, calculations (where appropriate) and recommendations when it comes to choosing a NIC load balancing and teaming type.

Virtual Port ID

Your VMs all have single vNICs, You have multiple physical switches, the pNICs from the servers are striped across them, the switches aren’t stacked/don’t have an awareness of each other/are from different vendors (point here, completely different, no collaboration between equipment - any brownfield environment).

Why?

Simple, a VM, when it is spun up is assigned out a VPID each VM gets a different port, when the number of VMs > number of NICs, cycle back to the start again.

It doesn’t break and will work anywhere, no special switch config or awareness required network-side.

Example

Server has 4 physical NICs, we are spinning up 5 VMs:

VM1 -> pNIC1

VM2 -> pNIC2

VM3 -> pNIC3

VM4 -> pNIC4

VM5 -> pNIC1

Cons

VM pinning to VPID means that if a super busy VM is on the same NIC as another busy VM, that’s just bad luck - nothing you can do about it.

Source MAC Hash

Same as scenario 1, except we want to account for VMs with multiple vNICs.

Why?

Also the same as scenario 1, with the exception that VMs have multiple vNICs

Example

A host has 4 physical pNICs, we are spinning up 3x VMs with 2x vNICs each. The VMKernel does a calculation based on the MAC of the source vNIC. For 4 pNICs it will use 4 as the modulus to which it will test the MACs against. (because MAC addresses are just hexadecimal numbers) - let’s say:

VM1-vNIC1 = 00:50:56:00:00:00

VM1-vNIC2 = 00:50:56:00:00:01

VM2-vNIC1 = 00:50:56:00:00:0a

VM2-vNIC2 = 00:50:56:00:00:0b

VM3-vNIC1 = 00:50:56:00:00:1e

VM3-vNIC2 = 00:50:56:00:00:1f

We would run mod(4) against each MAC to get the remainder, the remainder will be the pNIC ID that vNIC is assigned to. Excellent article here ↗.

Convert the hex to Base10:

VM1-vNIC1 = 00:50:56:00:00:00 -> 345040224256

VM1-vNIC2 = 00:50:56:00:00:01 -> 345040224257

VM2-vNIC1 = 00:50:56:00:00:0a -> 345040224266

VM2-vNIC2 = 00:50:56:00:00:0b -> 345040224267

VM3-vNIC1 = 00:50:56:00:00:1e -> 345040224286

VM3-vNIC2 = 00:50:56:00:00:1f -> 345040224287

Run a modulus of number of NICs against it:

VM1-vNIC1 -> 345040224256 mod 4 = 0

VM1-vNIC2 -> 345040224257 mod 4 = 1

VM2-vNIC1 -> 345040224266 mod 4 = 2

VM2-vNIC2 -> 345040224267 mod 4 = 3

VM3-vNIC1 -> 345040224286 mod 4 = 2

VM3-vNIC2 -> 345040224287 mod 4 = 3

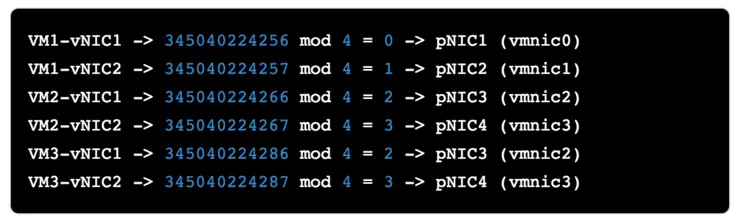

The idea is we will end up with something like this (perfect scenario):

VM1-vNIC1 -> 345040224256 mod 4 = 0 -> pNIC1 (vmnic0)

VM1-vNIC2 -> 345040224257 mod 4 = 1 -> pNIC2 (vmnic1)

VM2-vNIC1 -> 345040224266 mod 4 = 2 -> pNIC3 (vmnic2)

VM2-vNIC2 -> 345040224267 mod 4 = 3 -> pNIC4 (vmnic3)

VM3-vNIC1 -> 345040224286 mod 4 = 2 -> pNIC3 (vmnic2)

VM3-vNIC2 -> 345040224287 mod 4 = 3 -> pNIC4 (vmnic3)

Cons

So the workloads are pretty-evenly balanced, but again we are at the mercy of vNIC placement not actual load on the pNIC.

IP Hash ↗

Your physical switches that the hosts uplink to are stacked, or have stacking-like technologies (like Cisco vPC), if you have a single switch this will also work, or if you just have a pair of Dell 8024F/Cisco 3750-X that are stacked and create a LAG/Port Channel, and replicate the config on your vDS, that will also work.

Why?

This method will balance connections based on source and destination IP addresses across pNICs so single guests communicating with clients on different IP addresses will be distributed across pNICs.

Example

It will make a hash of source and destination IP addresses, then run an bitwise xor and modulus on those based on the number of pNICs in the server, so if it’s 4 like the above example, it will run (hex1 xor hex2) mod (4). This ensures (roughly) that each connection between a single source and different destinations are distributed across the pNICs.

Obviously, the guest and client IP remain the same throughout that particular communication, so that connection will stay pinned to its calculated pNIC, if a pNIC goes down, re-calc is run across the remaining live pNICs, pretty neat.

Let’s look at a practical example (Again, assuming host with 4 pNICs):

Client1 -> VM1 (10.0.1.1 -> 10.0.1.200)

Client1 -> VM2 (10.0.1.1 -> 10.0.1.201)

Client2 -> VM1 (10.0.1.2 -> 10.0.1.200)

Client3 -> VM1 (10.0.1.3 -> 10.0.1.200)

Let’s convert the IP addresses to hex:

Client1 = 10.0.1.1 -> 0x0A000101

Client2 = 10.0.1.2 -> 0x0A000102

Client3 = 10.0.1.3 -> 0x0A000103

VM1 = 10.0.1.200 -> 0x0A0001C8

VM2 = 10.0.1.201 -> 0x0A0001C9

Alright, let’s xor those values:

Client1 -> VM1 (0A000101 xor 0A0001C8) = C9 = 201

Client1 -> VM2 (0A000101 xor 0A0001C9) = C8 = 200

Client2 -> VM1 (0A000102 xor 0A0001C8) = CA = 202

Client3 -> VM1 (0A000103 xor 0A0001C8) = CB = 203

And now run a modulus on the resulting base10 numbers:

Client1 -> VM1 = (201 mod 4) = 1 = vmnic1

Client1 -> VM2 = (200 mod 4) = 0 = vmnic0

Client2 -> VM1 = (202 mod 4) = 2 = vmnic2

Client3 -> VM1 = (203 mod 4) = 3 = vmnic3

So, as you can see, even connections to the same VM, but from different clients will get distributed across pNICs. Therefore theoretically more than single pNIC throughput to one guest from multiple clients if connections are distributed across pNICs.

Cons

Again, at the mercy of a very busy client + server connection loading up one pNIC, harder to configure, requires specific physical switch and vDS config, doesn’t “just work”.

LBT/Physical NIC Load

This is the only option that is utilisation aware, it also requires no special switch configuration (same as Virtual Port ID/MAC Hash).

Initial placement of VMs uses the exact same calculation as Virtual Port ID.

Once a pNIC becomes 75% utilised for 30s then there will be a calculation run, and in a sort-of “network-DRS” kind of way, the connections will be shuffled around to try and create a more balanced pNIC load.

LBT investigates RX and TX individually. So, if RX is at 99% and TX is at 1%, average being 50%, RX is above the 75% threshold, therefore, the pNIC is marked as saturated.

Why?

It’s the only method that’s utilisation aware and actually balances load across pNICs.

Example

Take a server with 4 pNICs again, with the following pNIC utilisation levels:

vmnic0 -> 70% utilised

vmnic1 -> 80% utilised

vmnic2 -> 50% utilised

vmnic3 -> 65% utilised

When the calculation runs, vmnic0, vmnic2, vmnic3 will be seen as candidates for rebalancing, LBT will rebalance as it sees fit, let’s say one particular VM is using 15% of the bandwidth on vmnic1, a rebalance would look like so:

vmnic0 -> 70% utilised

vmnic1 -> 65% utilised

vmnic2 -> 65% utilised

vmnic3 -> 65% utilised

Pretty simple, however note, if you look at esxtop and find that you have a lot of traffic going out one vmnic and not others, this is because LBT only kicks in when a pNIC becomes saturated.

Thus you may end up with 3 pNICs with 0% utilisation and 1 pNIC with 72% utilisation, it just hasn’t cross the rebalancing threshold yet. But if it’s not causing contention, who cares?

Cons

Requires Ent+ licensing because it requires a vDS to use this mode.

LACP ↗

LACP mode allows you to use dynamic link aggregation groups from your physical networking infrastructure to your ESXi hosts.

LAG balancing is yet another set of distribution methods, not load balancing methods, this is a common misconception.

A list of all LAG distribution methods in ESXi (as of v5.5) can be found here ↗.

An important thing to note about LACP/LAGs on vDSs:

The LAG load balancing policies always override any individual Distributed Port group if it uses the LAG with exception of LBT and netIOC as they will override LACP policy, if configured.

Basically, if you have Network IO Control enabled or LBT on a port group these will take precedence over LAG balancing policies, for obvious reasons, to quote VMware:

These two configurations are going to load balance based on the traffic load which is better than LACP level load balancing.

Why?

You want to use dynamic LAGs from your physical network to your ESXi boxes, it will also allow VMs, (depending on the distribution type specified) and the workload running on the VM, to use more than 1 pNIC worth of bandwidth, whereas, if you were to use other methods (except IP-Hash which also has this trait) each VM will only be able to use 1 pNIC worth of bandwidth.

Example

As per our other examples, 1 server with 4 pNICs, we are using the Source and destination IP address and TCP/UDP port load balancing type. We will use a very “perfect” scenario, assuming that the calculation run will allow this method to work as optimally as possible.

Client1:1000 -> VM1:2000

Client1:1001 -> VM1:2001

Client1:1002 -> VM1:2002

Client2:1000 -> VM1:2000

Because LACP-hashing calculations are usually firmware specific, and quite often a “secret-sauce” kind of thing we can’t do a calculation that will hold true across manufacturers, chipsets, even releases of the same software. So we will assume that it will work as optimally as possible.

What we will see in our 4 pNIC server case is:

Client1:1000 -> VM1:2000 = vmnic0

Client1:1001 -> VM1:2001 = vmnic1

Client1:1002 -> VM1:2002 = vmnic2

Client2:1000 -> VM1:2000 = vmnic3

Note: this is a very perfect scenario, in reality, it will likely be nothing close to this, however the law of averages will say this can of course occur in some environments.

Cons

Some extra complexity at the physical network layer, and messing around with active/passive LACP sides, and Ent+ licensing is required as this is a vDS feature.

Honestly, if you were licensed for vDS and didn’t require VMs to have the possibility of having over 1 pNIC worth of bandwidth, then you would just use LBT mode.

Conclusion

If you’re licensed for vDS

- Use LBT, unless you have workloads that require more than 1

pNICof bandwidth, then use LACP.

If you don’t have vDS licensing

- If your network uses teaming/stacked switches, use IP-Hash (if you don’t mind the extra complexity).

- If your VMs have multiple

vNICs and you want to distribute them acrosspNICsuseMAC Hash(on non-stacked switches). - If you just have single

vNICs and non-stacked switches,Virtual Port IDit is.

I hope this helped, any questions, drop me a line below!

Why not follow @mylesagray on Twitter ↗ for more like this!